Nurses while checkung the progress of an expectant mother’s pregnancy at a hospital in Kampala city. PHOTO

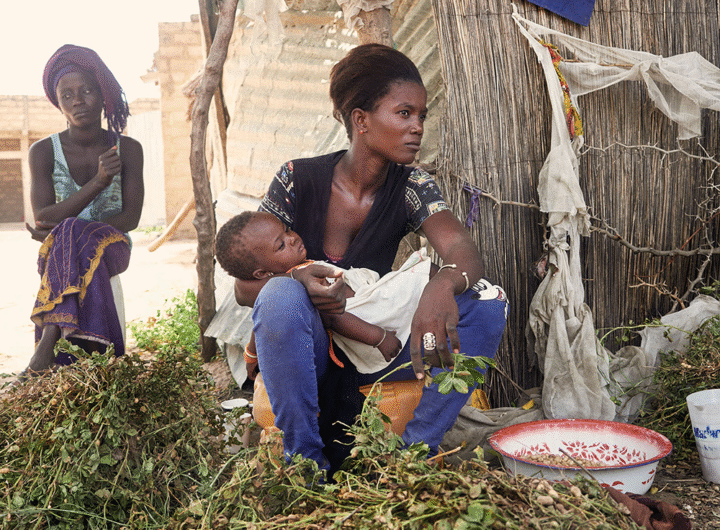

Nalubowa Sylivia was pregnant with twins by the time she arrived for delivery at the village health centre. This was her eighth pregnancy. But she soon ran into complications. She pushed one baby out but could not push out the second.

The health centre was in Maanyi, a small rural village in Busujju sub-county in Mityana and was not equipped for such emergencies. It could not do a caesarean birth because it lacked an obstetric surgeon and theatre and was manned by nurses not midwives.

Nalubowa was immediately referred to the nearest government hospital in Mityana town. A few hours after arriving at the hospital, Nalubowa and the unborn child were dead – another of the estimated 500 women who die in Uganda every year during childbirth.

mother in-law, Rhoda Kukiriza, was with her when she died in 2009. About 59 years old at the time, the now elderly 70 year old remembers the events as if they happened yesterday.

“We arrived at the big hospital as darkness gathered,” she recalls, “And the harassment started as soon as my daughter entered the labour ward.”

She remembers the nurses asking her to pay Shs 50,000 on the spot before her daughter could be helped. At the time, Rhoda says, Shs 50,000 felt like what a million shillings is today, and she only had Shs 30,000 left.

“Even when I pleaded and told them that they would get the money the following morning, they refused to attend to her saying they have heard those stories before,” she says, “The nurses instead walked away as my daughter tearfully pleaded for a caesarean section.”

“They asked for that money even after they had ordered me to buy gloves, razor blades, basins. I was practically buying everything.”

Kukiriza believes her daughter-in-law would not have died had she found the necessary facilities and attention needed for child birth in the government hospital.

“My daughter would not have died because I tried to bring her quickly to the facility,” she says.

Gov’t sued

Kukiriza retold her story on April 27 in Kampala, a couple of hours after civil society organisations (CSOs) that campaign against rampant maternal mortality cases went back to the Constitutional Court to file a case seeking to compel the government to provide more money in the budget for maternal care.

The CSOs are unhappy that the government provides only Shs724 million per year for reproductive and child healthcare which is about the cost of two SUVs that top Ministry of Health officials drive.

“This money is not sufficient to cater for maternal health,” says Patrick Rubangakene, the Budget Policy Specialist, Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group (CSBAG), a Kampala-based non-profit that tracks the health sector budget, “It is because of it that mothers dying during childbirth is still rampant in Uganda.”

“We could be losing more mothers,” he says, “relying on official statistics might not give a true picture.”

According to the most recent Health Sector Performance Report, of the 21 hospitals assessed, 496 mothers died while giving birth in FY 2019/2020 compared to 424 deaths in FY2018/2019.

In the latest report, Kawempe National Referral Hospital in Kampala registered the highest number of deaths (116) followed by Hoima.

“If Kawempe which is in the centre of the country loses this number of mothers, imagine what is happening beyond the city,” Rubangakene says. He told The Independent that all civil society is asking for is for Uganda’s health facilities to be fully equipped.

“Mothers are dying because of shortage of blood and yet the cost of a refrigerator and a power back-up system for Health Centre IVs is not beyond government reach,” he says, “Most operations are done at HC IVs but these are not fully equipped and do not have functional theatres while others don’t have the required human resource to run these facilities.”

“We need to ensure these theatres are functional so that our mothers can get the immediate service at HCIV instead of us relying on the national referrals or general hospital.”

“We already have a poor referral system. We don’t have functioning ambulances; that means services have to be delivered at HCIVs.”

“Improving the health units (HCIVs and HC IIIs) which ordinary Ugandans interface with would be the best way forward. It is important to create a unique vote for health with a proper accounting officer so that we are able to track the money.”

Peter Eceru, the Programme Specialist, Health and Human Rights at Centre for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD), a Kampala-based non-profit says they register hundreds of cases of pregnant women who have lost lives in health facilities and the stories are of the same script because the government has abandoned its responsibility of providing adequate health services to its citizens.

He says Uganda spends about Shs7.5 trillion every year on health but the government only contributes about 15%. The donors foot 42% of the budget while 41% is out of pocket payments by the citizens. The rest is contributed by health insurance schemes.

“Getting pregnant shouldn’t be a crime in Uganda; getting pregnant is supposed to be celebrated but for a bigger part of our community that has become a time to mourn,” Eceru says.

He says the government needs to provide money for three things: recruitment of more health professionals, providing blood women who need it, and providing medicine to women who are bleeding and need the bleeding to stop.

“That is what we are simply asking our government to do.” Eceru says, “The problem is not that we lack adequate resources, the challenge is prioritization. Once you don’t prioritize then you have the challenges Uganda is grappling with.”

Public health expert warns of increasing threat of hospital-acquired infections

Public health expert warns of increasing threat of hospital-acquired infections  Postpartum Psychosis: The Hidden Battle African Mothers Should Not Fight Alone

Postpartum Psychosis: The Hidden Battle African Mothers Should Not Fight Alone  It’s No Longer Just a Bet — It’s a Disease”: Pamela Udoka Sounds Alarm as Gambling Addiction Gains Recognition as Mental Disorder in Nigeria

It’s No Longer Just a Bet — It’s a Disease”: Pamela Udoka Sounds Alarm as Gambling Addiction Gains Recognition as Mental Disorder in Nigeria  𝐕𝐞𝐧. 𝐁𝐚𝐫𝐫. 𝐅𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐮𝐬 𝐎𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐚, 𝐏𝐡.𝐃., 𝐀𝐩𝐩𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐆𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐡𝐮𝐫𝐜𝐡 𝐨𝐟 𝐍𝐢𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐚. By Irodili C Iroegbu

𝐕𝐞𝐧. 𝐁𝐚𝐫𝐫. 𝐅𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐮𝐬 𝐎𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐚, 𝐏𝐡.𝐃., 𝐀𝐩𝐩𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐆𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐡𝐮𝐫𝐜𝐡 𝐨𝐟 𝐍𝐢𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐚. By Irodili C Iroegbu  Trump Undergoes MRI Scan Amid Renewed Health Speculations

Trump Undergoes MRI Scan Amid Renewed Health Speculations  Coalition submits unified cassava industrialisation policy framework to Senate

Coalition submits unified cassava industrialisation policy framework to Senate  TODAY IN HISTORY – 28th Oct, 2025 – AfricanWorldNews

TODAY IN HISTORY – 28th Oct, 2025 – AfricanWorldNews  Nigeria’s DSS Arrests Man Over Online Call for Coup Against Tinubu Government

Nigeria’s DSS Arrests Man Over Online Call for Coup Against Tinubu Government  AU Hails Biya’s Re-Election, Urges Dialogue as Protests Shake Cameroon

AU Hails Biya’s Re-Election, Urges Dialogue as Protests Shake Cameroon