By Ollus Ndomu

Malawi heads to the ballot on 16 September 2025 with the political atmosphere tightening by the day. The election will be the second under the reformed system introduced after the annulled 2019 vote. Over 7.2 million Malawians have registered, with women accounting for more than half of the roll.

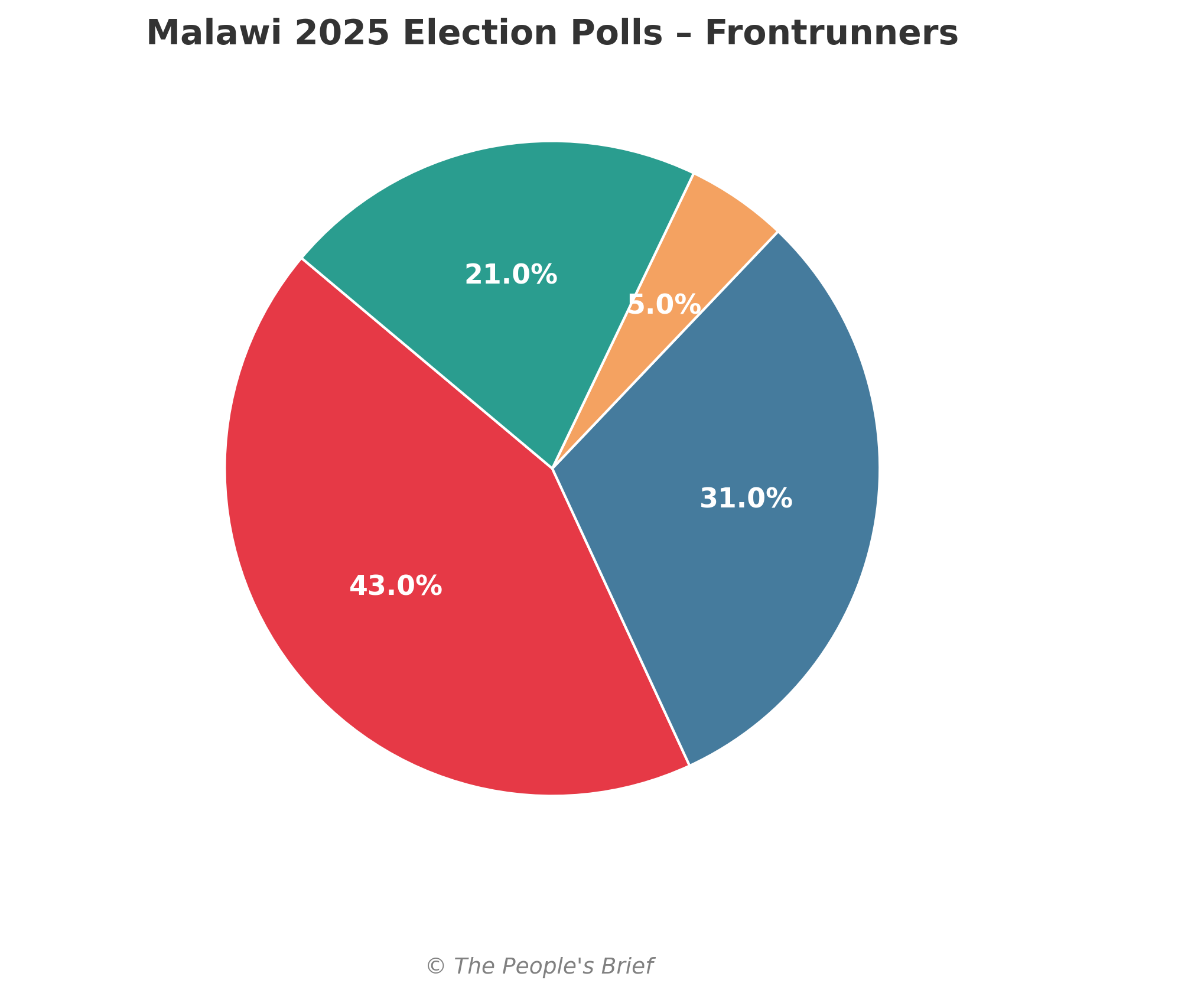

The race has taken a sharp turn. Peter Mutharika, the 84-year-old former president, is back in the spotlight. An IPOR opinion poll has placed him at 43 percent, comfortably ahead of incumbent Lazarus Chakwera who sits at 26 percent. Another survey showed Chakwera inching up to 31 percent, but still trailing significantly. Dalitso Kabambe, a technocrat and former central banker, hovers around 5 percent, while smaller parties are splintered across the margins.

The numbers tell a deeper story. In 2020, Malawians voted in fresh elections after the courts threw out the disputed 2019 poll. Chakwera rode a wave of hope, promising reform and renewal. Five years later, that goodwill appears to be slipping. Food shortages, soaring prices, and perceptions of slow delivery are dominating the political discourse. In a recent survey of 2,400 adults across 27 districts, 29 percent of respondents cited food insecurity as their top concern, another 29 percent pointed to economic management, while a staggering 51 percent said corruption would determine their vote.

Mutharika’s return is both a rebuke and a reminder. Critics point to his age and past record, yet supporters argue he represents a steady hand and a protest against unmet promises. Chakwera, meanwhile, faces the difficult task of convincing voters that his government deserves a second chance despite the economic turbulence.

The credibility of opinion polls has itself become political theatre. The ruling Malawi Congress Party (MCP) has accused the opposition of influencing survey results to create a bandwagon effect. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has dismissed those claims, framing them as excuses from a nervous incumbent. Even the British government has come under fire for commissioning a last-minute poll, sparking accusations of foreign interference.

Malawi’s constitution requires an outright winner to secure 50 percent plus one of the vote. With no candidate projected to reach that mark, a runoff looms as the most likely outcome. That would extend the contest into a bruising second round, with coalition building and cross-party bargaining determining the final winner.

For ordinary Malawians, the election is not about personalities but about survival. The message from the electorate is clear: deliver food security, restore economic stability, and take corruption head-on. Anything less risks rejection at the ballot.

With Malawi now entering the home stretch of a high-stakes campaign, the question is not just who wins, but whether whoever emerges can meet the demands of a restless electorate.

DHQ uncovers details of foiled coup plot against Tinubu

DHQ uncovers details of foiled coup plot against Tinubu  FCTA Workers, NLC Take Labour Dispute to Court, Demand Wike’s Exit

FCTA Workers, NLC Take Labour Dispute to Court, Demand Wike’s Exit  Rivers Power Play Puts Tinubu in a Political Tight Corner

Rivers Power Play Puts Tinubu in a Political Tight Corner  Rivers APC Hails Tinubu’s Stand, Says Presidency Has Settled Wike–Fubara Leadership Dispute

Rivers APC Hails Tinubu’s Stand, Says Presidency Has Settled Wike–Fubara Leadership Dispute  Africa’s Powerbrokers Rally Behind Museveni as Uganda Votes Him into a Seventh Term

Africa’s Powerbrokers Rally Behind Museveni as Uganda Votes Him into a Seventh Term  My appointor has the right to sack me — Wike Fires Back at Sack Calls, Dares Criticu

My appointor has the right to sack me — Wike Fires Back at Sack Calls, Dares Criticu  Zambia’s Hichilema’s Makes His Case: Stabilisation, Reform and the Road to 2026

Zambia’s Hichilema’s Makes His Case: Stabilisation, Reform and the Road to 2026  Onitsha Market Closure: Soludo Explains Rationale, Vows to End Sit-at-Home

Onitsha Market Closure: Soludo Explains Rationale, Vows to End Sit-at-Home  FIFA Rules Out World Cup Ban as Senegal Face CAF Sanctions Over AFCON Final Walk-Off

FIFA Rules Out World Cup Ban as Senegal Face CAF Sanctions Over AFCON Final Walk-Off  Nollywood Actress, Angela Okorie Reportedly Detained Over Alleged Cyberbullying Linked to Mercy Johnson Case

Nollywood Actress, Angela Okorie Reportedly Detained Over Alleged Cyberbullying Linked to Mercy Johnson Case