JESUS IS A BLACK MAN

QUESTION AND ANSWER (PART ONE)

I had the opportunity to have a direct and engaging conversation with Author TC Wanyanwu, a writer whose work continues to challenge long-held ideas about faith, race, and history. As the African proverb says, “Until the lion learns to write, the story will always glorify the hunter.” This interview reflects that moment, the lion speaking.

As a Pan-African journalist, poet, and activist, and someone who has known Author TC for the past two years, I have come to recognize him as a bold thinker and disciplined researcher. This is Part One of a highly interactive conversation.

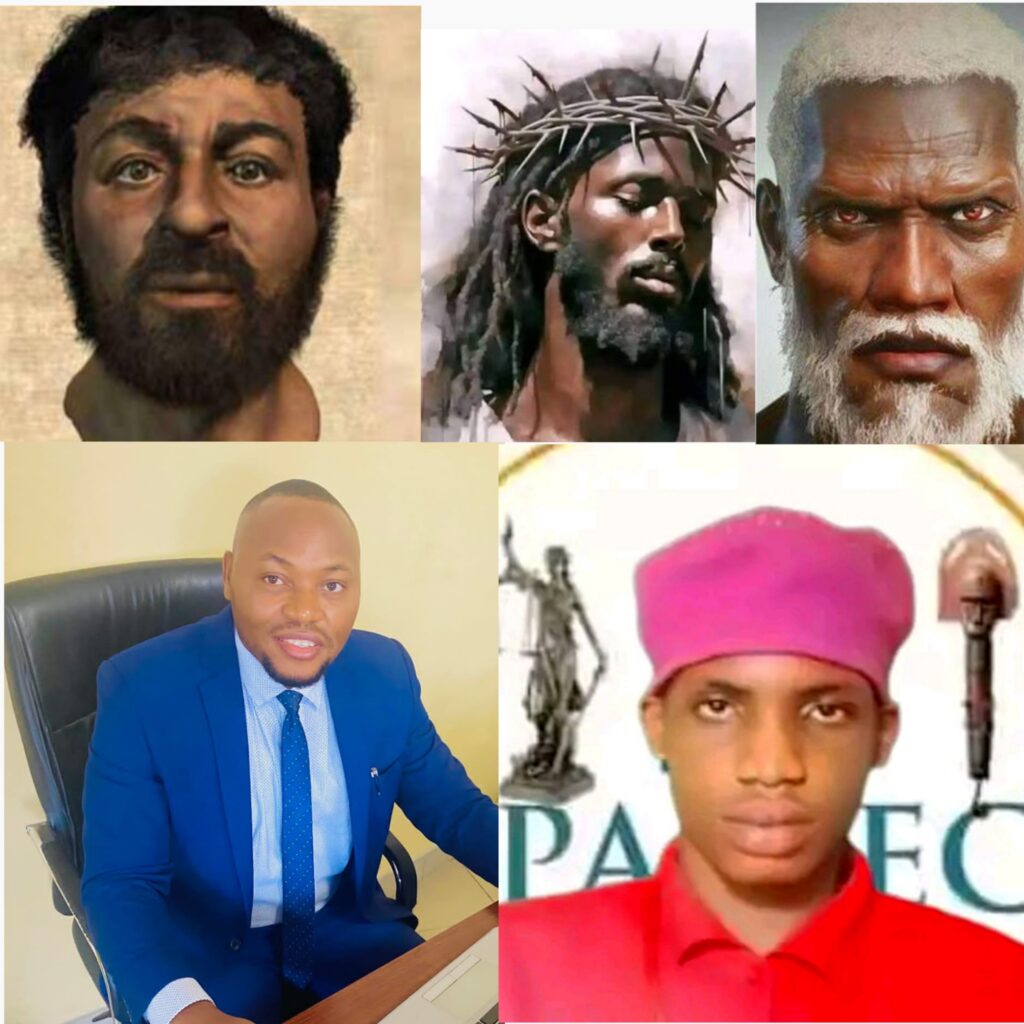

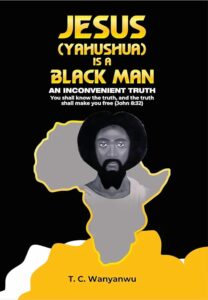

His book, Jesus Is a Black Man, has gained worldwide recognition and has become one of the best-selling and most talked-about books on religion and identity, easily found with a simple Google search.

In this interview, TC Wanyanwu answers 30 hard-hitting questions, speaking clearly, directly, and without apology.

Irodili: Your book Jesus Is a Black Man became widely known and sparked conversations all over. Before this, had you written any other works that gained attention, or was this really the first book that brought you into the spotlight? Can you walk us through how this book came to be such a success?

TC Wanyanwu: Before Jesus is a Black Man I’d written and worked on smaller essays and poems, but this book was the first to catch wide public attention, partly because it touched a nerve by linking faith, identity, and history in a way many people hadn’t seen together before.

Irodili: When you decided to write that Jesus was a Black man, what was the first piece of evidence or research that made you start thinking in that direction? How did you begin your investigation into something that most people take for granted?

TC Wanyanwu: The idea started when I noticed that most people don’t really think about the real place and time Jesus lived in. Many people-especially atheists-often say Jesus was just a myth and not a real person at all. That pushed me to read about the history and geography of his world, and to look at how colonial thinking shapes what we believe. From there, I began asking a simple question: who actually benefits from the version of Jesus we are taught to accept?

Irodili: Throughout history, we see Jesus depicted as white, and churches even have white statues of Jesus, Mary, and the angels. Why do you think these images became so common, and could they be more about cultural influence or power than historical accuracy?

TC Wanyanwu: Those white images became common because art follows culture and power – European artists, churches and empires shaped Christian visual culture for centuries, so appearance was often dictated by who made the pictures, not by careful historical description.

Irodili: Can you point to any part of the Bible where Jesus’ skin colour or ethnicity is clearly described? If not explicitly, what clues do you use to support your argument, and how do you interpret them?

TC Wanyanwu: There are several Bible verses that give a paint-by-numbers physical description.

(4.1). Jesus’ ethnicity is clearly Black Jewish, not White European or American

– Matthew 1:1–17 traces Jesus’ genealogy through Abraham and David (Song of Solomon (Song of Songs) 1:5 says:“I am dark, yet lovely, O daughters of Jerusalem, dark like the tents of Kedar, lovely like the curtains of Solomon.”)

– Luke 4:16 shows Jesus (Yahushua) worshipping in the synagogue, as a Black Jew

– John 4:9 identifies Him within Jewish–Samaritan ethnic tensions

(4.2). Jesus was born in the Middle East Israel that shares same tectonic stone with Africa- merely separated by Suez Canal in Egypt, a man-made waterway connecting the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea.

– Matthew 2:1 — “Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea”

– This places Him geographically among Black Middle Eastern peoples, not White Europeans

(4.3). Isaiah 53:2 suggests He had no striking physical appearance for admiration

– “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to Him” Yet majority ignorantly worship an adorable White European movie actor they claim is Jesus

– This verse implies Jesus did not stand out physically.

(4.4). Revelation 1:14–15 is symbolic, not biological

– “His head and hair were white like wool… his feet like bronze” A typical description of a Black man

– This is apocalyptic imagery describing glory and authority, not race or skin tone though.

I also look at contextual clues — region, ancestry, language, trade and local anthropology — and read descriptions that are metaphorical alongside historical data to build a plausible picture.

Irodili: Beyond the Bible, are there other religious or historical texts that strengthen your claim? For instance, does the Quran, Jewish writings, or early historians provide evidence, and how do you investigate these sources to make sure they’re credible?

TC Wanyanwu: Yes – I examine non-biblical sources (Jewish historical writings, Roman accounts, and where relevant Islamic tradition and early church fathers). I treat each source by its genre, date, and bias, weighing corroboration and internal consistency before drawing conclusions.

Irodili: In your book, you claim the Igbos are the true Israelites. What historical, linguistic, or cultural evidence led you to this conclusion? Can you take us step by step through the reasoning that convinced you?

TC Wanyanwu: For the Igbo-Israel thesis like several other tribes mentioned in my book, I trace claimed cultural parallels, oral traditions, linguistic echoes, shared rites and migration stories, then weigh them against mainstream archaeology and genetics – I present the parallels as suggestive and worthy of more study, not as unquestionable proof.

Irodili: When discussing race, do you mean to say that white people are not Black, or are you specifically pointing out Jesus’ ethnic background? How do you define these categories carefully?

TC Wanyanwu: I’m not saying “white people are not Black.” I’m arguing about historical ethnicity and the likely appearance of a Galilean Jew. I define categories carefully: “Black” in the book is used to reclaim an African-centered image and to interrogate racialized power – I try to distinguish ethnicity, skin tone, and modern racial categories. I am currently working on a new book titled: Black is not ‘skin colour’ but a people with common feature (Brown, Red, Yellow, Dark & Light Skin) from Africa major, Asia minor, & Middle East.

Irodili: Many people think that saying Jesus was not white is controversial, and some even call it racist. How do you respond to that? When investigating history, how do you separate facts from the emotions or biases people may bring?

TC Wanyanwu: I understand the controversy. I respond that pointing out Jesus likely wasn’t white is not an attack; it’s corrective history and a challenge to visual traditions shaped by empire. Separating facts from emotion means being transparent about sources and honest about where interpretation begins.

Irodili: Martin Luther King Jr. fought against racism and was assassinated. Decades later, do you think racism still affects how people perceive Jesus’ image? How did you investigate the social and psychological factors behind these perceptions?

TC Wanyanwu: Racism still shapes image and imagination. I looked at 20th and 21st-century art, missionary histories, and social psychology studies to see how race, authority, and representation interact – the persistence of a white Jesus often reflects historical hierarchies more than theological necessity.

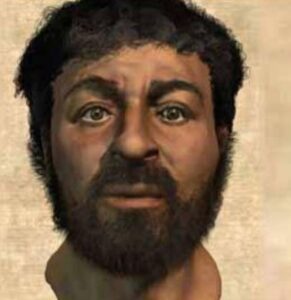

Irodili: Everyone has seen pictures of Jesus, but how can we really know what he looked like 2,000 years ago? Considering there were no cameras and the earliest Christian art appeared centuries later, what kind of historical or archaeological evidence could support the claim that Jesus was Black?

TC Wanyanwu: We can’t know with certainty, but archaeology, contemporary Jewish skeletal and skeletal-anthropological studies, and descriptions of regional phenotype give us reliable likelihoods. Combined with the social context (Semitic peoples of the Levant), we can make a historically informed reconstruction — always probabilistic, not absolute.

Irodili: Your book claims Jesus was Black, but the idea of race as we understand it today didn’t exist 2,000 years ago. If we study the ethnic and cultural background of first-century Jews, can we confidently place him into today’s racial categories, or is this a modern interpretation?

TC Wanyanwu: Absolutely correct – the modern racial map didn’t exist then. I use ethnic and geographic markers (Galilean Jew, Semitic ancestry) and then carefully discuss how those categories sit with modern racial terms, warning readers against anachronism while explaining why reclaiming a darker image matters socially.

Irodili: You highlight olive-brown skin as evidence that Jesus was Black. But if we examine the anthropology of people living in ancient Palestine, does that skin tone clearly fit the modern concept of “Black,” or is it somewhere in between?

TC Wanyanwu: Olive-brown skin in first-century Palestine would likely have looked somewhere between what we think of today as European and sub-Saharan African. In other words, Jesus’ skin tone wouldn’t match modern stereotypes of “Black” or “white” exactly—it was in the middle. But the point isn’t to fit him neatly into modern racial categories. My book emphasizes that portraying Jesus as non-European challenges a long-standing Eurocentric assumption that has shaped art, teaching, and even church practices for centuries. Highlighting a Middle Eastern or African appearance helps correct that default and allows communities to see themselves reflected in his story.

Irodili: The Bible uses descriptive phrases like “hair like wool” or “feet like bronze.” If we investigate the original Hebrew and Greek words, can we rely on these as literal evidence of physical traits, or might they be symbolic or metaphorical?

TC Wanyanwu: Phrases like “hair like wool” or “feet like bronze” are poetic and must be checked in the original languages and contexts. I treat them as possible physical clues but also as symbolism; I show both readings and let the evidence and genre guide the interpretation. (Refer to Answer 4:4)

Irodili: Historians and forensic experts have attempted to reconstruct Jesus’ likely appearance using archaeology and scientific studies. Does your book engage with these scholarly reconstructions, or does it rely more on your own interpretation? How did you investigate and compare these sources?

TC Wanyanwu: I engage with scholarly reconstructions and forensic studies and compare them to historical evidence and the iconographic record. Where forensic scholars reconstruct a first-century Semitic face, I reference that work and explain where my cultural reading aligns or diverges.

Irodili: Your book carries a strong cultural and identity message for Black people. If we dig deeper, do you think you were presenting pure history, or was the goal also to inspire pride and cultural identity? How do you investigate where history ends and cultural motivation begins?

TC Wanyanwu: It’s both history and identity work. I set out to correct historical assumptions but I also wanted to open a space of cultural pride and theological reorientation for Black readers – I’m explicit about where I move from historical argument to cultural affirmation especially in my new book titled: Black Jesus WHITEWASHED: Poetic Reflections on Race, Religion, and Awakening https://www.amazon.in/gp/aw/d/B0F3JLYFXC

Irodili: Even if Jesus was not white, does this information actually change the meaning of his teachings? When you investigate, how do you weigh the historical facts against the spiritual lessons?

TC Wanyanwu: The teachings of Jesus stand firm regardless of his skin tone. Love, justice, mercy, humility, and compassion do not rise or fall on complexion. What my book argues, however, is that historical correction matters-not to rewrite morality, but to reshape belonging. When we restore context, we challenge who has been centered, who has been excluded, and how entire communities have been taught to see themselves in the gospel. Correcting the image does not alter the ethical core of Jesus’ message; it clarifies it, deepens it, and allows more people especially marginalized Black people to recognize that the Gospel were always meant for them too.

Irodili: If we look at reactions from different Christian communities around the world, what conflicts or patterns emerge when the idea of a Black Jesus is presented? Did you investigate these responses, and what did you find most surprising?

TC Wanyanwu: Reactions vary: some communities welcome the reclamation, others resist or fear politicization. I map those responses in the book and was most surprised by how defensive some institutions became when a visual tradition was questioned rather than theological doctrine.

Irodili: With limited evidence about Jesus’ actual appearance, how much can we truly know? If we follow the trail through archaeology, early Jewish history, and ancient Christian writings, which conclusions are safe, and which are speculative?

TC Wanyanwu: With limited direct evidence, certain things are safe (Jesus was a Middle Eastern Black minority Jew who lived under Roman rule); other conclusions (precise complexion or hair texture) are more speculative. I label which claims are stronger and which are interpretive.

Irodili: If the idea of a Black Jesus becomes widely accepted, how could that reshape Christian communities globally? Did your investigation consider potential social, psychological, or cultural consequences?

TC Wanyanwu: A widely accepted image of a Black Jesus could shift liturgy, iconography, pastoral care and self-image in many churches; it could also provoke backlash. I explore social and psychological consequences — greater inclusion for some, discomfort for others — and argue the conversation itself is valuable.

Irodili: What methods did you use to cross-check the Bible, historical documents, and anthropological evidence to ensure your claims are solid? How did you investigate conflicting information?

TC Wanyanwu: My methods: cross-referencing scripture with contemporaneous histories, archaeology, art history and anthropology; checking original languages; consulting experts; and being transparent about uncertainty. Conflicts are handled by assessing date, proximity to events, and internal consistency.

Irodili: Some critics say your sources are symbolic, opinion-based, or unreliable. How do you respond, and how did you investigate to confirm which sources are strong evidence?

TC Wanyanwu: I welcome critique. When sources are symbolic or late, I flag them as such. I emphasize converging lines of evidence rather than single, isolated texts, and I present the weakest claims as hypotheses rather than proved facts.

Irodili: While researching, did you come across evidence that challenged your thesis? How did you investigate these contradictions and decide which direction your book should take?

TC Wanyanwu: Yes — I found contrary evidence: later Greco-Roman portrayals, some textual traditions, and scholars who argue for a typical Levantine look. I engaged those contradictions in the book, weighing them and sometimes revising my language from categorical to probabilistic.

Irodili: Oral traditions and cultural memories often play a role in history. How much weight did you give to stories passed down through generations, and how did you investigate their reliability?

TC Wanyanwu: I give oral traditions careful, contextual weight: they’re culturally important and can preserve memory, but they need cross-checking with dated archaeological and documentary evidence. I treat them as valuable leads, not alone decisive proof.

Irodili: Could early Christian art, statues, or paintings have been intentionally altered to convey spiritual messages rather than real appearances? How did you investigate the difference between art as devotion versus art as evidence?

TC Wanyanwu: Absolutely. In the early centuries of Christianity, art was not meant to work like a photograph. Most early Christian paintings, icons, and statues were created to teach faith, inspire devotion, and communicate spiritual ideas-not to preserve Jesus’ physical appearance. Artists used symbols their audiences already understood. For example, light or whiteness often stood for purity, holiness, or divine presence, not literal skin colour. In my investigation, I treated religious art as language, not evidence. I compared images of Jesus from different regions and time periods-Rome, Byzantium, Ethiopia, and later Europe-and noticed how his appearance changed to reflect the culture, theology, and power structures of each society. When Jesus looks Roman in Rome, African in Ethiopia, or European in medieval Europe, it tells us more about the worshippers than about the historical man. So I drew a clear line between art as devotion and art as documentation. Devotional art expresses belief, values, and theology; historical evidence comes from geography, anthropology, and first-century context. Art helps us understand what people believed about Jesus-but it cannot, on its own, tell us exactly what he looked like.

Irodili: Are there examples of other historical figures whose appearance was misrepresented over time? Did investigating these cases help you understand how Jesus’ image might have been changed?

TC Wanyanwu: Many figures have been visually reimagined: the Buddha, Alexander, even the Pharaohs in some later Western art. Those cases show how power, travel and imagination reshape faces over time — a pattern useful for reading changes in Jesus’ image.

Irodili: How do you investigate the difference between symbolic descriptions in the Bible and literal physical traits? What clues do you look for?

TC Wanyanwu: I approach it the same way we normally do in everyday reading: by asking what kind of writing this is and what the author is trying to do. The Bible contains different types of writing-history, poetry, prophecy, letters-and each uses language differently. Poetry and prophecy often use images and metaphors, while historical writing is more straightforward. So I look at the wording in the original language and the section where it appears. If a description shows up in a poetic or prophetic passage, it is more likely symbolic-meant to communicate meaning, not physical detail. If it appears in a historical setting, written plainly and repeated by different writers who are not copying each other, then it carries more literal weight. In simple terms: one dramatic image in a poem is not the same as a repeated description in historical accounts. When a detail shows up once in metaphor, I treat it carefully. When similar descriptions appear across different sources and contexts, I take them more seriously as physical traits.

Irodili: When you reference other texts, like the Quran or historical writings, how do you investigate their accuracy and context?

TC Wanyanwu: For other texts I read them in their historical-linguistic contexts, check accepted translations, consult specialists, and pay attention to when and where the texts were written to guard against taking late or polemical passages as evidence for first-century reality.

Irodili: How did you investigate the claim that the Igbos are descendants of the Israelites? Which pieces of evidence were the strongest and why?

TC Wanyanwu: On the Igbo-Israel claim I looked at oral genealogies, ritual parallels, onomastic similarities, and missionary and colonial records; I found intriguing overlaps but not definitive proof. I present the strongest pieces as reasons for more interdisciplinary research, not conclusive mapping.

Irodili: Could historians’ personal or cultural biases influence how they describe Jesus’ appearance? How did you investigate and account for these biases in your research?

TC Wanyanwu: Yes — every historian brings perspective. I examine historians’ backgrounds, funding, religious or national agendas, and the time they wrote to filter bias. I also favour primary sources and archaeological data over single interpreters with clear axes.

Irodili: Looking back, if you were to redo this investigation today with modern tools and scholarship, would any of your conclusions change? How would you investigate differently?

TC Wanyanwu: If I redid it with new tools (genetics, broader archaeological surveys, or more digitized manuscripts) I’d be even more cautious about categorical claims and would frame more conclusions as probabilistic. New methods would likely refine rather than overturn the core message: that the white European Jesus is a later cultural construction and that recovering the historical context matters.

Tanzania Poised for Historic Energy Breakthrough as $42bn Mega LNG Deal Nears Final Signature

Tanzania Poised for Historic Energy Breakthrough as $42bn Mega LNG Deal Nears Final Signature  DOMINION CITY AMUWO ODOFIN PRESENTS — A SUNDAY OF RESTORATION & RENEWAL

DOMINION CITY AMUWO ODOFIN PRESENTS — A SUNDAY OF RESTORATION & RENEWAL  Somali Troops Kill Over 130 Militants, Crush Al Shabaab Attack on Kudhaa

Somali Troops Kill Over 130 Militants, Crush Al Shabaab Attack on Kudhaa  DR Congo Offers Major Mineral Assets to US Investors in Strategic Partnership

DR Congo Offers Major Mineral Assets to US Investors in Strategic Partnership  Assemblies of God Bars Pastors from Marrying Outside the Church

Assemblies of God Bars Pastors from Marrying Outside the Church  Ibeh Ugochukwu Bonaventure on Troco Technology: Building Trust Where Nigerians Once Took Risks

Ibeh Ugochukwu Bonaventure on Troco Technology: Building Trust Where Nigerians Once Took Risks  Onitsha Market Closure: Soludo Explains Rationale, Vows to End Sit-at-Home

Onitsha Market Closure: Soludo Explains Rationale, Vows to End Sit-at-Home  FIFA Rules Out World Cup Ban as Senegal Face CAF Sanctions Over AFCON Final Walk-Off

FIFA Rules Out World Cup Ban as Senegal Face CAF Sanctions Over AFCON Final Walk-Off  Nollywood Actress, Angela Okorie Reportedly Detained Over Alleged Cyberbullying Linked to Mercy Johnson Case

Nollywood Actress, Angela Okorie Reportedly Detained Over Alleged Cyberbullying Linked to Mercy Johnson Case  FCT Strike Persists as Workers Ignore Court Order, Keep Pressure on Wike

FCT Strike Persists as Workers Ignore Court Order, Keep Pressure on Wike